I saw an infographic floating around last week with the 2021 vintage of PE-backed consumer IPOs, suggesting consumer IPOs were a private equity firm offloading a loser onto you, the public shareholder. As you might expect, given how sugar-high the investing environment was at that point, those 2021 consumer stocks have not performed well. Maybe I spent too much time on reddit (editor’s note: he spends too much time on reddit) but the concept of “private equity” is becoming “socialism” for a different crowd – an ill-understood, oft-blamed concept in irrelevant situations. Especially because there’s relatively little initial sell-down for PE firms at the time of IPO, and most of these stocks went south quickly, I thought the criticism might not be well-founded (i.e. private equity lost alongside public investors, and did so in public view). So I decided to dive in.

Shout out to Alex Fabry for inspiration here – he and I didn’t overlap at Charlesbank / we’ve never actually spoken but I’ve enjoyed reading his content over the last year. And shout out / credit to The Silent Shopper for pulling together the initial infographic. Hit me up – would love to talk shop with both of you!

For most of the consumer IPOs above (which have indeed done poorly), the explanation of the stock price performance is pretty clear to me.

- Rent the Runway: Killer combination of relatively low gross margins (~30%) and tough LTV / CAC math, so it’s been (not-so) shockingly hard for it to get to profitability. Just because something is a subscription business doesn’t mean you should value it like software.

- Leslie’s: Went public when everyone was cooped up with COVID and outdoor home recreation was one of the few safe options, and pool-related spending has backed off from the growth they experienced at IPO (not to mention some execution issues the last few years and a tough balance sheet).

- Olaplex: Competed in a very trendy category, TikTok decided their products made your hair fall out, and customers moved on to the next brand. (If there was one in this group I wouldn’t bet against, it’s this one, because I think there’s a path to becoming a multi-branded platform).

- Oatly: Investors somehow temporarily forgot that milk is a commodity product, and adding “oat” in front of that wouldn’t change the category fundamentals. It also turned out it was hard to scale manufacturing to cover fixed costs while maintaining quality (see basically every plant protein company).

- Bumble: I have no idea what’s going on at Bumble and I don’t want to know (I’ve been in a relationship since 2011 and married since 2017, so I am supposed to be ignorant on all things related to online dating).

That leaves us with Portillo’s. This one is the most interesting to me for many reasons:

- Chicago is living rent-free in my head right now. I’m a Green Bay Packers fan. I have a feeling we’ll see Packers / Bears round three in a couple weeks, and I cannot wait.

- My dream job (or one of them) is CFO or Head of Investor Relations at a growth-oriented, publicly traded restaurant chain. Accomplishing this dream will not be a 2026 goal (that post will probably come a bit late this year) but I figured maybe if I start putting it out in the world and acting like I can do it, it could eventually happen. There are many “what if’s” in careers, and one of the ones I dwell on the most was not advocating for myself harder to join a restaurant case at BCG. Most staffing was done regionally, those projects were led by teams based in the South region (I was in the Northeast), and I just never fought hard to make it happen. Maybe I’d be further along on that journey if I did. Lesson learned.

- Portillo’s unit economics are unlike basically anything else in fast casual, so it’s an interesting case study / point of comparison to the broader restaurant industry.

- The product is good. Damn good. Like, cult following good. And multiple locations are apparently under construction in the Denver area. Side note – one very small but underrated part of living in Colorado is that it’s a natural expansion zone for regional restaurant chains from the West Coast, Texas, and Midwest. So we can have In-N-Out Burger, Culver’s, and Whataburger in the same glorious town center in Colorado Springs. The European mind cannot comprehend this.

One of the best inclusions in an S-1 I’ve seen in a while.

A Brief History of Portillo’s

For those of you who haven’t been lucky enough to experience it, Portillo’s is a fast casual restaurant with deep Chicago roots. The company was founded in the 1960s and was privately held and run by the Portillo family for over 50 years, before they sold a majority stake to Berkshire Partners in 2014. When Berkshire acquired the business, it was basically a Chicago-area phenomenon, with a couple locations in California.

Many a private equity firm has been seduced by the family-owned, regional brand that hasn’t scaled geographically yet. The whipped cream on the cake shake for Berkshire was Illinois’ climate and demographic trends. Illinois has had a flat to slightly declining population for a long time, both in Chicago and rural areas. On its face, that seems bad for Portillo’s, given their significant concentration in Illinois. However, people leaving Illinois were moving somewhere, either other spots in the Midwest, or retiree-friendly states like Arizona and Florida. Berkshire was betting that those departed former Illinois denizens still craved their hot dogs without ketchup and would bring their friends to a nearby Portillo’s if one opened in their new state.

This seemed like a good bet. Over the next seven years, Portillo’s expanded to 67 locations, including sites in Arizona, Florida, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, and at the time of the S-1 filing, they marketed the total expansion opportunity to be 600 units. Investors in the IPO were betting on this expansion potential. However, the S-1 dropped an important clue about what these units might look like.

Unit Economics

The geographic expansion strategy Portillo’s embarked on was not without risk. After all, while basically everyone in Chicago had heard of the brand, a much lower percentage of people in those new markets had. Lower brand awareness means less restaurant traffic out of the gate, which means lower revenue. The real estate playbook in the Chicago area might not work outside the area due to different construction firms and timelines and potentially different kinds of nearby tenants to evaluate. Lastly, there’s a proximity and oversight point that’s hard to quantify. When a location is down the street from headquarters and close to many other locations, there are lots of resources to help fix emerging operational issues, and lots of experienced eyes on the operations. In new, far-flung markets, this benefit doesn’t exist.

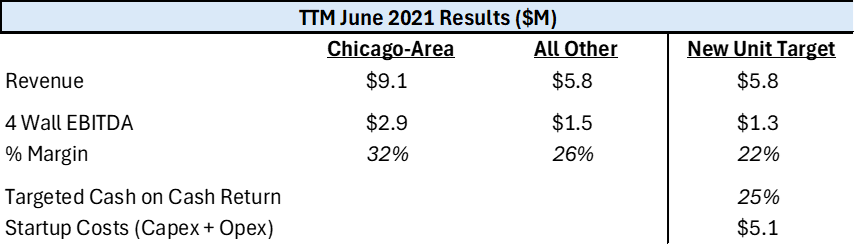

Locations outside Chicago were generating about $5.8 million in revenue and $1.5m of restaurant level / four-wall EBITDA. Chicago-area locations were putting up nearly 2x that profit. A clear gap in performance, likely attributable to the above factors. And while a 25% unlevered ROIC for new locations isn’t bad, getting nearly 50% ROIC (as implied by the Chicago-area performance) would’ve been stellar. One could’ve made an argument that new markets could eventually look like Chicago when brand recognition improved, but at IPO, they certainly weren’t there.

For those with some restaurant industry experience, the point I’m about to make will be obvious. But these are highly unusual per-location results for someone selling sandwiches, fries, and shakes. If you want to click through a ranking, here’s some industry context – but Portillo’s outranks literally every other major restaurant brand on its unit-level sales. This is Chick-Fil-A territory (their average non-mall location did $8.1 million per year in 2021 revenue, but in total, the average was below Portillo’s).

Revenues that are off the charts, and $5 million a pop to open (for context, if you bought the real estate for a Taco Bell or Wendy’s and opened one, that might be $3-4 million at the high end, and if you were leasing, it might be $1.0-1.5 million) – one thing Portillo’s is not is an easily franchised concept. All locations were company owned and operated, and this capital-intensive, operationally intensive approach to growth means that opening more than a handful of locations per year is probably outside the realm of what Portillo’s could reasonably do. This is a pretty different playbook than most PE-backed restaurant concepts, which potentially propelled Portillo’s toward an IPO exit when capital markets allowed.

The IPO

Portillo’s went public in October 2021, with a $430 million offering that paid down debt, cashed out a portion of Berkshire and the family’s ownership, and cleaned up the incentive plan to match a typical public company structure. Pretty straightforward. What wasn’t straightforward, in hindsight, was the valuation multiple.

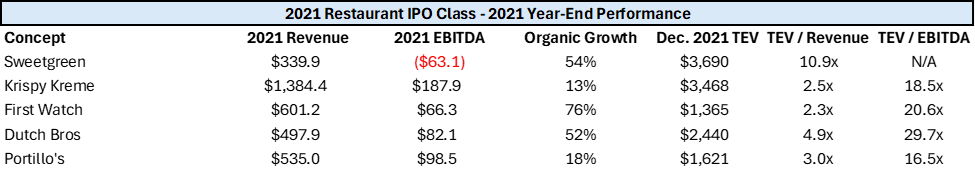

Krispy Kreme, First Watch, Dutch Bros, and Sweetgreen also all IPO’ed in 2021, and all were investor-backed beforehand. (As an aside – why weren’t these on that infographic that prompted this deep dive? Did someone cherry-pick their comps to make an argument? Finance people would never do that). Krispy Kreme and Sweetgreen have also been tough stories (down 80%), but First Watch is only down 25% since IPO (not good, but not catastrophically bad, particularly when compared to general 2021 euphoria), and Dutch Bros is up considerably since IPO.

To normalize a bit for post-IPO trading, I looked at year-end 2021 multiples. IPO’s are intentionally priced below where underwriters and sellers believe the company should trade post-IPO. Sellers are effectively giving the new shareholders a slight discount, to entice them to participate in a situation where there’s some information asymmetry.

What stands out?

- First – Sweetgreen somehow was trading like a software company in 2021. Except it wasn’t even a “rule of 40” company – the revenue growth of 54% plus EBITDA margin of negative 19% is less than 40. So it wouldn’t even be a good software company, if salads were recurring revenue, which they are not. That 10.9x revenue multiple was nuts. I hope I’m brave enough to short stocks the next time these opportunities arise.

- Second – Portillo’s had lower growth than most of the comp set – which ties back to the capital intensity of new units. It’s way easier to pump out a new coffee stand or salad shop than a Portillo’s in terms of finding adequate space, hiring that sheer number of employees, and financing the construction and setup. Much of the organic revenue growth shown here was driven by new units, not comp-store sales.

- Third – Portillo’s wasn’t trading at an eye-popping EBITDA multiple, though its growth was significantly more capital intensive than say, Krispy Kreme, which operated only about half of its locations and franchised the rest.

It’s not as if Portillo’s went public with total irrational exuberance, at least not on its face. So what happened?

Post-IPO Performance

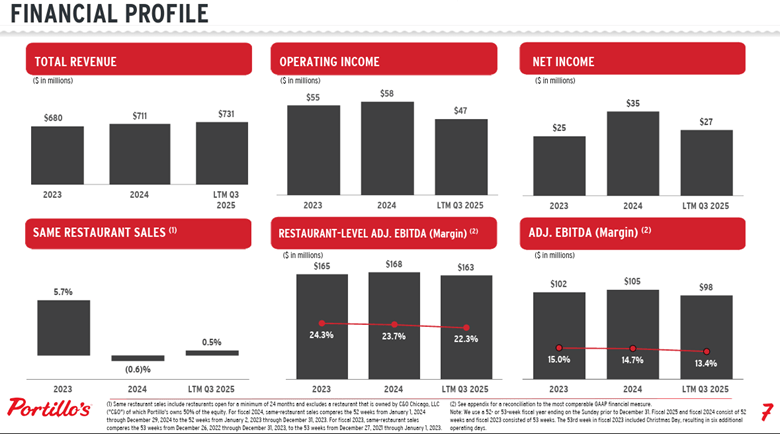

Portillo’s has been a public company for 4+ years now, and the stock price would indicate there’s been a material change in performance. So where does it show up? The easy answer is same-store sales. The last two years in particular have not been kind on that front, with an inflection from mid-single digit growth to no growth / slight decline. Just scanning the last couple earnings calls transcripts, transaction volumes are declining by 1-2%, offset by a few percentage points of price increases and slight pressure from changes in product mix. So people are coming to existing locations slightly less frequently, Portillo’s increased their prices to offset food and labor cost inflation, and people are buying slightly cheaper menu items / fewer items per visit. That’s not a recipe for growth stock success, but also not out of step with the trends in fast casual right now.

Second, new locations have underperformed. It turns out that the pace of growth pursued over the last few years was too aggressive in new markets, with new locations that opened too close to each other both in distance and timing, which led to slower ramps / restaurant-level margin compression as well as sales below underwriting expectations. Also – you might remember that 2021 Adjusted EBITDA was also in the $100 million range. So the company has grown store count by nearly 50%, seen same-store growth go to zero, and been flat on EBITDA for four years.

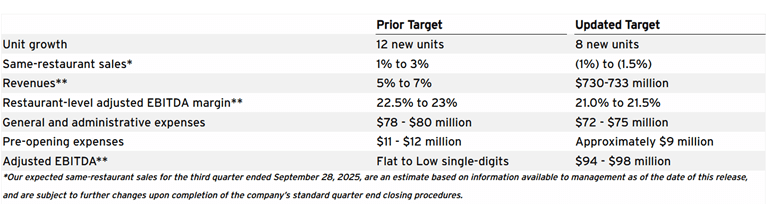

In September 2025, Portillo’s reduced its full year 2025 targets pretty significantly, reducing new locations, comp-store sales, and restaurant-level margins. The crazy thing was that the “prior target” was announced in August, concurrent with Q2 earnings. Either something changed considerably in those 30 days, someone missed some big flashing red lights on performance trends, or there was some disagreement at the top about whether or not to change guidance. Either way, not the way to inspire public markets confidence. Given the trend and the continued uninspiring outlook, it’s unsurprising that two weeks later, longtime CEO Michael Osanloo was replaced by board member Mike Miles, in an interim role.

On their next earnings call in November, Portillo’s specifically pointed to tough times in its Texas locations, but noted that they didn’t see any particular demographic driving the change in performance (unlike some other restaurant concepts, where Millennials and Hispanic customers in particular have shown up less in recent quarters).

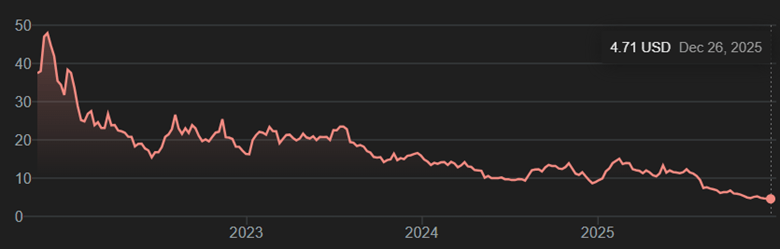

Today, Portillo’s has a market cap of about $355 million, about $300 million in net debt, and is trending toward $96 million of EBITDA for the year. On one hand, 7x EBITDA feels like an absolute bargain – a few years ago I could barely find a decently sized multi-site consumer franchisee for 7x EBITDA, let alone a company that controls its brand and has significantly higher growth potential. But somehow they’re also going to spend $100 million on capex in 2025, which doesn’t quite align with the pace of openings, at $5-6 million per opening (spending on 15-20 this year? IR team – maybe something to add in a future deck!). Given the business isn’t cash flow positive right now, slowing the pace of new location growth until there’s more confidence in what new units outside Chicagoland will look like at maturity feels prudent. Until then, this ugly chart (stock price since IPO) is kind of the story.

Summary

Portillo’s still has its insane location-level sales, a decent consumer value proposition, and lots of territories it still hasn’t conquered. But right now, it’s facing the issue that many other regional restaurant IPOs have faced as they’ve scaled (Del Taco expanding outside SoCal and Papa Murphy’s outside the Pacific Northwest definitely come to mind) – the inability to replicate insane unit level economics in new markets where they don’t have decades of brand recognition and consumer loyalty.

I’m just hoping that the slowdown in new location development won’t delay their planned Colorado openings. Because the only way I’m moving to Chicago is if Portillo’s hires me to be part of the turnaround (do they even accept Packers fans?).