Over the last few months, there have been some unexpected and spectacular collapses – Sonder getting rugpulled by Marriott, First Brands promising the same receivables to multiple different factoring firms and generally doing shenanigans…no shortage of stuff to dive into. But the Tricolor Auto collapse, in which a large private company went up in smoke in a Chapter 7 (aka the “not coming back from this” version) bankruptcy back in September, stood out to me for a few reasons:

- I’m about a month into a new job, and a lot of my time has been spent taking over other people’s large, complex Excel models. While I never worked in investment banking, I was around IB-trained PE investors for long enough to make very specific spreadsheet hygiene and formatting guidelines feel like second nature to me. It took me about seven seconds in this role to realize I was the only one here who knew these “rules”, and that was going to make the already fun task of taking over someone else’s model that much harder. (I’ll save my rant on the Indirect formula being really dumb and sloppy for the Twitter comments). Inevitably, there are hardcodes that aren’t identified on the first pass, data sources that aren’t as clear to the new spreadsheet owner as the creator of the analysis, and at best it’s slow progress, at worst it’s wrong or incomplete. The fact that part of the Tricolor fraud was discovered because a senior director on their finance team forgot to update a column in a spreadsheet before sending it to a lender…big yikes on the fraud, but also “yeah man, I get how that happens”.

- Consumer finance, particularly subprime finance, is something I find both intellectually and morally interesting. And businesses that are consumer finance businesses masquerading as retailers are even more interesting. From a moral perspective, I find the “payday loans should be regulated out of existence” crowd to have too narrow of a perspective at best, and are guilty of infantilizing the poor, at worst. Just because someone is poor, it doesn’t mean they can’t make a reasonably informed decision about their finances. In fact, because money is so tight, they’re arguably more attentive, whereas when a middle-class or rich person makes dumb financial decisions, it’s rarely noticeable because it’s a relative drop in the bucket. And just like a payday loan may be someone’s best potential path to credit, in a pinch, it also tracks that for someone who needs a car but has a checkered credit history (or none at all), the solution is a higher interest rate loan. So this is not a multi-thousand word missive on why Tricolor should’ve never existed.

For those who didn’t track this story, Tricolor Auto was a retailer of used cars that specialized in “buy here, pay here” lending. Simply put, because the customers that retailers like Tricolor serve generally wouldn’t be considered good credit risks by banks, Tricolor makes the loans directly to their customers. The “buy here” references the fact you show up to a Tricolor used car lot, and the “pay here” references that the loan payments on the car are made to Tricolor. In some ways this looks like the captive auto lenders that major automakers own, except for the very important details that 1) auto manufacturers are franchisors with captive finance arms, and branded auto dealerships are franchisee retailers that retain very little / no risk on the loans, whereas “buy here pay here” used car dealers sell cars and hold the credit risk on the related loans and 2) auto manufacturers are using low-cost financing to drive higher-margin vehicles out the door to low-risk customers, whereas “buy here pay here” dealers are making significant profit on loans, as long as they stay current. But as you might expect for a high-risk segment, many of these loans did not, in fact, stay current.

While anything but a household name, Tricolor had grown to 65 locations since its founding in 2007. This included a location down the street from me on W. Colfax Ave that I drive by to go to my favorite coffee shop. To draw the picture for non-locals, Colfax was once dubbed the “longest, wickedest street in America” and still retains some of this, uh, charm, today.

While relatively new to Colorado, Tricolor was #3 in used car market share in Texas and California, with 60,000 outstanding loans and over $1 billion in annual revenue. Not bad for a private company, except for the secret ingredient. In order to fund that growth, Tricolor obviously needed a lot of used cars. And since its customers were most definitely not paying upfront for cars, Tricolor had its own significant financing needs. In order to buy inventory, Tricolor took out loans that were collateralized by its unsold inventory – pretty straightforward. However, Tricolor’s larger pool of assets was the loans taken out by the buyers of its cars. Naturally, they securitized some of these loans and sold them off, and used others as collateral for lines of credit, similar to any other asset-based revolving loan with an advance rate.

Asset-based lenders typically lend at a percentage of the assessed value of the receivables and inventory in their collateral package. The more predictable the value of the underlying asset / higher “quality”, the higher the advance rate. Let’s say you are a consumer products company and you sell to retailers. Your accounts receivable would be comprised of amounts from various retailers, who are due to pay you for the goods you sold them. If this consumer products company wanted to borrow against its receivables, a bank might lend a high rate, say 85-90 cents on the dollar, against Amazon receivables. This is because Amazon is clearly a creditworthy counterparty and will eventually pay you, and the bank is pretty certain the loan will be money-good. They might lend a lower percentage against receivables from a mom & pop retailer or a distressed retailer’s receivables, for the same reason (harder to know whether that retailer will actually be around to pay you). And they may not lend at all against past-due receivables, on the principle that it’s reasonably certain that those retailers aren’t going to pay those invoices (maybe they’re out of business, maybe our products showed up damaged and they’re mad at us, either way, the bank doesn’t want it to be their problem).

Back to Tricolor, who had a lot of credit lines that were backed by its receivables. Except instead of Amazon or mom & pop retailers, the other side of these receivables were people buying used cars with high interest rate loans. So not exactly Amazon or other AAA credit entities. As you might expect there were many defaults and late payments, and Tricolor was in the business of thinking about its business as a portfolio, where there would always be some portion of late payments or non-payments on its loans. But the banks that lent Tricolor money didn’t want to lend against its bad loans, just its performing loans. And here’s where the first fraud comes in, as part of its normal course reporting to its banks, Tricolor said many of its non-performing loans were actually being paid on time, so that the banks continued to extend them more credit. Not good. And even worse for the company to that when the CEO / Founder is on the board of one of the banks he’s lying to! There’s a common critique of public company boards for being too chummy and disengaged, but the folks at Origin would’ve probably preferred a disengaged board member to one that enriches the company he founded and runs at their expense.

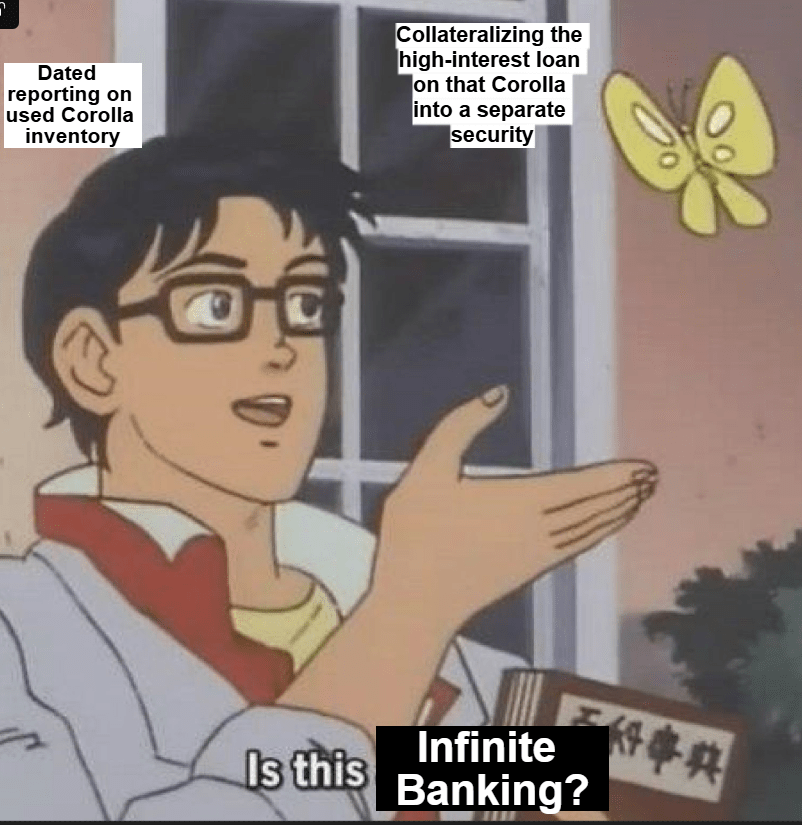

That apparently wasn’t enough fraud, so the Tricolor team took a page out of the First Brands playbook and pledged the same collateral to multiple parties. The simple way to do this: if a car was unsold, it was in inventory, and was pledged to a credit line. Once sold, that car was no longer on their lot / no longer an inventory asset, and instead Tricolor had an asset that was a receivable on its balance sheet for the loan it made to the customer. Tricolor’s “innovation” was simply not bothering to tell the bank with the inventory financing line that the car sold (and therefore should come out of the borrowing base analysis), while simultaneously getting credit for the auto loan from a different financing.

A misclassified non-performing loan here, a double-pledged Corolla there, and Tricolor allegedly had $1.4 billion of actual collateral and $2.2 billion of “pledged” collateral back in August. For the humanities majors, that’s $800m of fraud. So the logical question one might ask –how did this get so big and go on for so long? According to the SDNY, who seem like they have a treasure trove of colorful and self-incriminating emails on this one, Tricolor had successfully pulled the wool over the eyes of both its auditors and lenders back in 2022, similarly using non-performing loans to borrow money to plug a hole in the balance sheet. At the very least, by this summer, Tricolor had a lot of practice at doing fraud.

This brings us to the 3rd week of August, where it all began to crash. And for the senior director who was sending files to the lenders and is now one of the parties facing charges, no doubt a very bad day in a series of bad days. One of the lenders discovered $63 million in loans that Tricolor had marked as “current” aka being paid on-time, but hadn’t had a payment in six months, because their balance was staying constant across the borrowing base analyses they submitted over time. It turns out that it wasn’t enough to mark the loans as “current” – in order to maintain the illusion, Tricolor needed to reduce the balances of loans in the spreadsheet, which this fellow failed to do. This prompted Tricolor’s CEO to say that this was “the stupidest fucking thing he had ever heard” in a leadership team meeting, and then added said senior director to the conference call presumably to berate him in front of the whole team. Yikes. And yes, this senior director is cooperating with the SDNY investigation (as is his boss, the former CFO), and hmmm I wonder why he’s doing that.

The week continued with the CEO getting on the phone with said lender to try and assuage them by saying “if we were trying to commit fraud, we wouldn’t be so stupid as to keep the same balances on there…nobody would be that stupid.” Except…yeah. In hindsight, the argument wasn’t very convincing, because the company collapsed a couple weeks later. But in the moment, it apparently got the lenders to stop pressing, because after all, how else do you respond to a CEO that you have a significant business relationship with, when he says that?

Sadly – for my intellectual curiosity, this feels like pretty garden-variety fraud. On one hand, they apparently were able to get away with it for multiple years. On the other hand, the leadership team is facing decades in prison. If you made it this far and you weren’t sure, this is a cautionary tale and not a roadmap or a how-to guide! As I dug in here, the malfeasance itself was less interesting than I was expecting or hoping, and I think there’s a lesson in there – there’s only so many ways to commit fraud, and perpetuating a fraud seems way less intellectually interesting and fun than figuring out how to, you know, actually make this business work. And there’s almost certainly a business that works in this market, even with some level of charge-offs and late payments.

For a relatively unknown brand in a part of the economy that most of the intelligentsia doesn’t really think about, Tricolor has gotten a decent amount of press. But what I haven’t seen much speculation on is what led them to start doing fraud in the first place. Ironically, back to the politics, Tricolor’s need to amp up the fraud in 2025 was probably brought on, at least in part, by ICE crackdowns. After all – about two-thirds of Tricolor’s customers didn’t have a credit score, most of Tricolor’s customers were in Texas and California, a lot of Hispanic immigrants live in those states, immigrants are significantly less likely to participate in the traditional financial sector…not much of a leap to assume many of those non-performing loans were made to people no longer in the US, and therefore had little reason or means to continue paying back their loan.

I’m just going to end with this image because politics creates strange paradoxes and bedfellows, and asking Elizabeth Warren which of these two groups she wants to support might cause her brain to explode.

Innocent until proven guilty…

https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/ceo-cfo-coo-charged-connection-billion-dollar-collapse-tricolor-auto – SDNY Press release (link at the bottom with full report)

20060504_financialaccess.pdf – Brookings Institute report on financial access for immigrants