I was having a conversation recently and was asked what I thought a good return on invested capital (ROIC) was, in a private equity context (no, this isn’t quite what I talk about with the boys on the weekend). I paused, pondered, and didn’t have a great answer other than “it depends” and “you know it when you see it”.

I had to think for a few reasons – one, because I normally see this metric applied within a company context (what’s the cost of doing a specific initiative, and what’s the benefit), two, it’s kind of a way of talking about multiples (albeit EBIT less taxes) but makes you sound bookish, and three, my brain immediately went to Return on Net Assets (“RONA”), which I think is actually a more interesting metric for comparing across sectors. For those who haven’t used it, RONA is basically earnings divided by net working capital and net PP&E. Basically, how much profit does the net asset base allow you to generate.

On some level, I don’t think my stumble is a bad answer to the question that was asked or the one I thought was asked – an asset-intensive business like a distributor is always going to have a lower return on net assets than a software or IT services business that has limited hard assets. That doesn’t mean that software or IT services is fundamentally a better business than a distributor – I would rather be selling aerospace fasteners than, say whatever corporate training software Pluralsight is selling. But on a relative basis, in my view it’s an interesting metric to compare companies within the same sector, to see who’s doing better.

The reasons I don’t simply think a high ROIC or RONA is automatically a sign of a great industry or company is that it could signal a low quality business or a barrier to entry, and that margin could get competed away.

I have been meaning to dig into the Zips Car Wash bankruptcy for the last few weeks and this conversation further prompted me. What’s the connection?

Sometime four or six years ago (don’t remember when, but I was in my office, so it probably wasn’t 2020!), I started to dig into the car wash industry. At this point, Mister Car Wash was a proven PE-backed platform but the industry was otherwise very fragmented. The relatively new express tunnel wash format created a standardized, low labor operating model, and layering a subscription model on top created significant revenue visibility. Layer on top of that the general trend toward consumer wanting “do it for me” versus “do it yourself” solutions, and a new industry was starting to bloom.

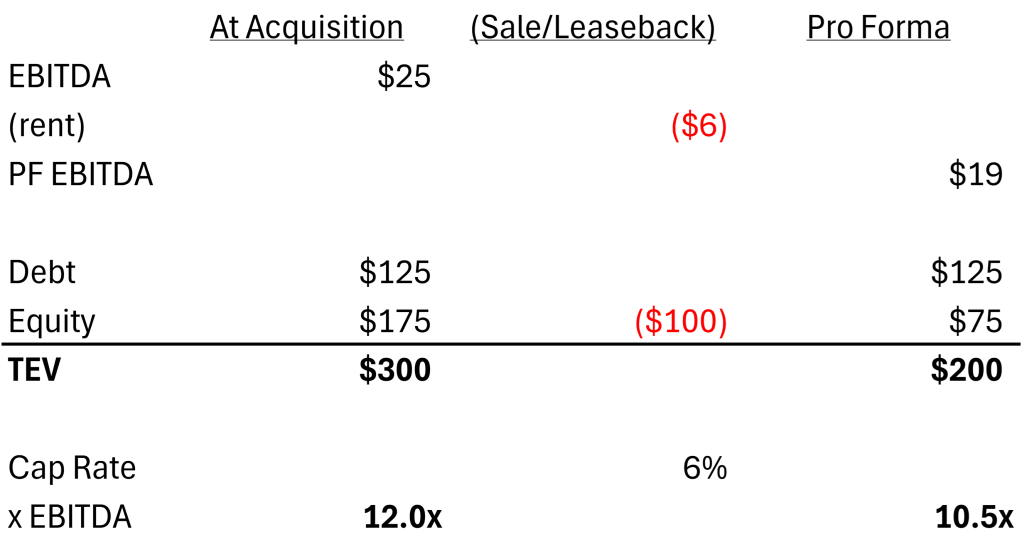

I remember talking with a lower middle market banker about a platform acquisition in the space – it was on the smaller end for Charlesbank but I wanted to learn more about the sector, and there weren’t a ton of bigger companies out there, anyway. I was getting mentally ready to start working on my investment committee presentation when the conversation turned to the company’s real estate, which this founder still happened to own. The obvious play here would be to do a sale leaseback as the real estate market was valuing car wash real estate at a cap rate well in excess of the expected multiple for an operating car wash business. So this was an easy way to reduce the equity account and multiple (and improve the ROIC) but also made the equity investment opportunity too small for me. So I put this opportunity and sector aside, and then over the next few years watched the car wash sector go absolutely nuts, with de novo buildouts and consolidation over the next few years.

Rough math on how a sale-leaseback can bring down an acquisition multiple

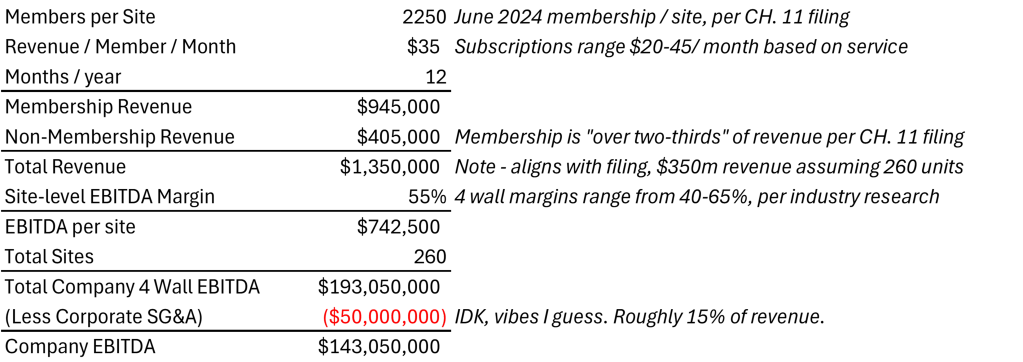

So this brings us back to Zips – which was one of the earlier PE-backed platforms, and the 5th largest operator of express car washes in the US. Atlantic Street Capital made its initial investment in May 2020, acquiring a majority stake from the Company’s founders. By this point, Zips was already a consolidator, having grown to 185 locations over a series of 40 acquisitions in the 2010s. Over the next few years, Atlantic Street supported the business with additional equity for acquisitions, bringing the total store count to 260, taking revenue to $345 million. The typical EBITDA margin for an express car wash chain is in the 40-50% range, so perhaps Zips had $150 million of EBITDA at this point. The rough breakdown of unit economics (based on some napkin math and what’s in their filings) and company-level profitability is below.

Rough Math on Zips’ Revenue Build

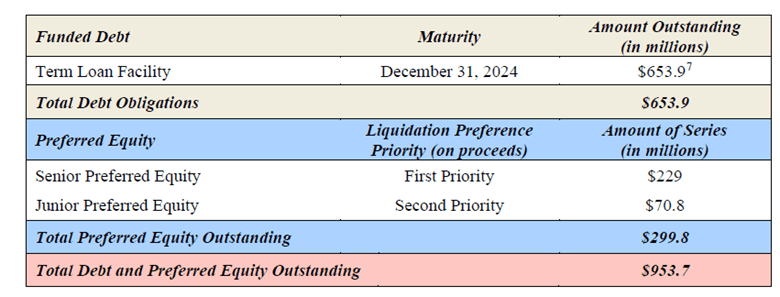

If my estimated $140-150 million of EBITDA at peak is true, raising $650 million of debt (snip below from Zips’ First Day Motions) doesn’t seem wild. So – what happened to earnings?

First, Zips didn’t effectively hedge its floating rate debt, and interest costs on its term loan hit $93 million in 2023, up from $59 million in 2022. With over $650 million in debt, this is pretty expensive debt too (14%, so my guess is that either there’s some bridge loan that wasn’t so temporary, or some mandatory prepayment embedded in this number). Either way, there goes a LOT of cash flow.

Second, inflation. While there aren’t a ton of operating levers, labor (the biggest cost driver excluding rent) and chemicals (actually pretty low, probably less than $1 per wash) no doubt increased in cost over the last few years. Why not raise prices? Well…car washes are somewhat discretionary, particularly in markets like the southeast where you aren’t washing road salt off the car. When combined with all the new sites coming online in the industry (remember, awesome ROIC!) I can see why operators, particularly those of sites that had been open for a few years, being reticent to fully raise prices when new competitors were opening. Especially because…

Third, more operators competing for fewer consumers. Zips locations were concentrated in the Southeast, where on average it’s easier to build a new car wash – less environmental permitting required. And when a new location that’s a little more convenient pops up, guess what – that’s where you’re going. There’s virtually no difference in consumer experience in car washes – I can’t even think of things beyond price, length of line, and whether the vacuums are working.

The term loan lenders are going to end up owning all of the equity in Zips with the preferred equity as well as the common equity getting wiped out, so if I were guessing, that EBITDA has been cut in more than half.

The car wash industry represents two topics within investing I think about a lot – first, how to think about industries where both supply and demand are growing rapidly, and second, what I think of as “the lemming effect”.

In an emerging sector where the average unit has high ROIC relative to other sectors, juiced by low-cost debt and sale leasebacks, plus simple operations and recurring revenue, of course a lot of different operators will rush in to plant their flag. And they don’t do it in a coordinated way. So yes, while there are nearly 300 million cars on the road in the US, a consumer that is looking for new things to outsource for relatively low cost, and a situation where new units can stimulate demand (i.e. you might wash your car if it’s on your way home, but not if you have to drive 10 minutes out of the way), it’s also easy to see how the market model could break. Funnily enough, Zips’ own Chief Development Officer warned against over-building in a Bloomberg article roughly a year ago – indeed, a survival of the fittest in certain trade areas. Sounds like he knew from personal experience.

This gets to why a consensus “hot” industry where everyone piles in isn’t always a good buy. In private equity, there’s always a “next buyer” to think about – definitionally, investors need to sell the companies they are invested in to earn a return for their limited partners. And when supply and demand are growing at the pace the car wash industry was growing a few years ago, a ton of new middle market platforms popped up (look at this list, look at some of the founding dates!). In a “land grab” industry, the inevitable pace of development is going to slow down, the valuation of companies in the industry will be driven on the cash flows of the existing units, versus that and the option value from future development. Hence, significant risk of EBITDA multiple compression at exit. Additionally, there are only so many large-cap PE buyers of platforms, so if yours isn’t a top performer, there’s a risk of getting stuck. And as Zips illustrated, it gets a lot harder to out-compete a sea of well-capitalized PE backed competitors.

Predicting both what a future buyer is going to want in 3-5 years, but isn’t so well-known or competitive now that multiples are crazy high or the car wash building dynamics are in play, is kind of what makes the investors’ job hard, but interesting.